May 8, 2020 — 12 minutes read

java concurrency

Part 4 in a series of articles about Project Loom.

In this part we re-implement our proxy service with non-thread-blocking asynchronous java NIO.The companion code repository is at arnaudbos/untangled

If you’d like you could head over to

Part 0 - Rationale

Part 1 - It’s all about Scheduling

Part 2 - Blocking code

Part 3 - Asynchronous code

Part 4 - Non-thread-blocking async I/O (this page)

Part 5 - Reactive Streams

機織り

Yanagawa Shigenobu CC0 1.0

Table Of Contents

Starting from where we left in the previous entry, we can say that Asynchronous API are nice

because they don’t block the calling thread. But an asynchronous API is not a guarantee that it will not block

other underlying threads. Thus, the problem of memory footprint, context switches and cache misses of kernel

threads remains.

I also wrote this:

There’s a reason why both sync/async and thread-blocking/non-thread-blocking are often mixed-up: today, the only—i.e. built-in— way to execute

non-thread-blockingcode on the JVM is to useasynchronousAPI.

Let’s implement our use case once again (see part-2) with an asynchronous and non-thread-blocking API:

Java NIO.

You can find the complete source code for this sample here.

Java NIO

Actually, most of the code is the same as in the previous implementation. The API being asynchronous, we keep the many callbacks to pass around and business logic to cut into pieces.

The crux of this API change lies in the code handling the HTTP requests and bubbles up in the callback interface.

asyncNonBlockingRequest

I’ve been told that the slightly bulky and indented code I had put here at first, which illustrated, for dramatic effect, what callback hell looks like, could be a bit hard to digest at the start of a blog post. So I did my best to split it in several snippets.

public static void asyncNonBlockingRequest(

ExecutorService executor,

String url,

String headers,

① RequestHandler handler

) {

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

println("Starting request to " + url);

URL uri = new URL(url);

SocketAddress serverAddress =

new InetSocketAddress(uri.getHost(), uri.getPort());

② AsynchronousSocketChannel channel =

AsynchronousSocketChannel.open(group);

③ channel.connect(

serverAddress,

null,

new CompletionHandler<Void, Void>() {

...

}

);

} catch (Exception e){ ... }

});

}

- Unlike

asyncRequestfrom the previous entry,asyncNonBlockingRequestdoesn’t take aCompletionHandler<InputStream>but aRequestHandlerparameter. We’ll see why shortly. - Also unlike

asyncRequest, which uses aSocketChannel, this code opens anAsynchronousSocketChannel.

AsynchronousSocketChannel#openopens a channel (analogous to a file descriptor) in non-blocking mode by default. - We asynchronously establish a connection to the remote address.

channel.connect( // See previous snippet

serverAddress,

null,

new CompletionHandler<Void, Void>() {

@Override

public void completed(Void result, Void attachment) {

ByteBuffer headersBuffer =

ByteBuffer.wrap((headers + "Host: " + uri.getHost() + "\r\n\r\n").getBytes());

ByteBuffer responseBuffer =

ByteBuffer.allocate(1024);

④ channel.write(headersBuffer, headersBuffer, new CompletionHandler<>() {

@Override

public void completed(Integer written, ByteBuffer attachment) {

if (attachment.hasRemaining()) {

⑤ channel.write(attachment, attachment, this);

} else {

⑥ channel.read(

responseBuffer,

responseBuffer,

new CompletionHandler<>() {

...

}

);

}

}

@Override

public void failed(Throwable t, ByteBuffer attachment) {...}

});

}

@Override

public void failed(Throwable t, Void attachment) {...}

});

- The connection has been established. We can asynchronously write data to the channel (i.e. send the request).

- However, we may not be able to write the whole request (slow network, congestion, who knows), so we should continue until we are sure that the request has been sent entirely.

- As soon as the request has been sent, we start listening for the answer, so we asynchronously read from the channel for incoming data.

channel.read( // Se previous snippet

responseBuffer,

responseBuffer,

new CompletionHandler<>() {

@Override

public void completed(Integer read, ByteBuffer attachment) {

⑦ if (handler.isCancelled()) {

read = -1;

}

if (read > 0) {

attachment.flip();

byte[] data = new byte[attachment.limit()];

attachment.get(data);

⑧ if (handler != null) handler.received(data);

attachment.flip();

attachment.clear();

⑨ channel.read(attachment, attachment, this);

} else if (read < 0) {

try {

channel.close();

} catch (IOException e) {

}

⑩ if (handler != null) handler.completed();

} else {

channel.read(attachment, attachment, this);

}

}

@Override

public void failed(Throwable t, ByteBuffer attachment) {...}

});

- When data comes in, we have to make sure that the asynchronous call made by the caller has not been cancelled.

Because if it has, there is no point in consuming the content. This is the first reason whyRequestHandlerreplacesCompletionHandler: more control. - For each incoming data chunk, we send it to the caller so it can decide what to do (decode, aggregate, batch?, etc).

This is the second (and last) reason whyRequestHandlerreplacesCompletionHandler: handling HTTP content as it arrives from buffers/network. - We may not have consumed the whole response, so we need to check if there is more.

- When we are sure that no more response data remains, we can notify the caller that the call is finished.

The amount of incidental complexity contained in this implementation is incredible. We introduced asynchronous

programming in the previous entry. Now we introduce a new callback interface with more methods: RequestHandler.

Why not stick with CompletionHandler<InputStream>?

Why add void received(byte[] data); and force callers to deal with byte array?

But why?

You may be thinking that using a non-blocking SocketChannel would have been enough. Like this:

SocketChannel channel = SocketChannel.open(serverAddress);

channel.configureBlocking(false);

And that channel.socket().getInputStream() on top of it would return a nice InputStream

instance with non-thread-blocking read, write, etc. operations.

Unfortunately, this is not possible. From Socket#getInputStream we can read:

/**

* Returns an input stream for this socket.

*

* If this socket has an associated channel then the resulting input

* stream delegates all of its operations to the channel. If the channel

* is in non-blocking mode then the input stream's {@code read} operations

* will throw an {@link java.nio.channels.IllegalBlockingModeException}.

*

* etc.

*/

public InputStream getInputStream() throws IOException {

// ...

}

We want a non-blocking channel/file descriptor, so we can’t use this pattern. We are left with the choice of using

SocketChannel's read and write operations, or AsynchronousSocketChannel's.

SocketChannel's read and write operations don’t ensure that the given ByteBuffer will be fully filled or drained,

respectively. Sending the whole request and reading the whole response would require either looping or submitting

the operations to the executor.

Looping would be akin to busy waiting and would therefore hog the thread/CPU and prevent other tasks to run, so

submitting read and write operations to the executor is the best approach.

AsynchronousSocketChannel's read and write operations work the same, but they are already asynchronous. Which means

there’s no need to submit the operations to the executor manually.

It doesn’t make much of a difference, but that, plus not having to call channel.configureBlocking(false); was simpler

so I choose the later.

We’ll see later why this is a mistake and has a major drawback related to its recursive nature.

New callback interface

There are only two services in our use case: CoordinatorService and GatewayService.

In this implementation, both make HTTP calls using asyncNonBlockingRequest and must therefore provide a

RequestHandler.

Aggregating

Implementers not willing to stream the content to their callers should maintain an internal state aggregate of

the data. This is what CoordinatorService#requestConnection does.

It takes a simple CompletionHandler<Connection> parameter, because users of this service (getConnection callers) are

only interested in the completion of the call: when the response has been fully received.

void requestConnection(String token, CompletionHandler<Connection> handler, ExecutorService handlerExecutor) {

① StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder();

② asyncNonBlockingRequest(boundedServiceExecutor,

"http://localhost:7000",

/*headers*/ String.format(HEADERS_TEMPLATE, "GET", "token?value=" + (token == null ? "nothing" : token), "text/*", String.valueOf(0)),

new RequestHandler() {

@Override

public void received(byte[] data) {

try {

③ result.append(new String(data));

} catch (Exception e) {

failed(e);

}

}

@Override

public void completed() {

Runnable r = () -> {

if (handler != null)

⑤ Connection conn = parseConnection(

result.toString().substring(34)

);

};

if (handlerExecutor!=null) {

④ handlerExecutor.submit(r);

} else {

r.run();

}

}

/* isCancelled and failed methods are trivial */

});

}

- Instantiate an

StringBuilderto hold the content of the token response before parsing it. - Execute the HTTP request from a thread in the

boundedServiceExecutorpool. - However small, there’s absolutely no guaranty that the whole response will be filled

into the buffer. That’s just the way network buffers work.

TheStringBufferaggregate the substrings received by each successful read operation. - Execute the callback and parsing (see #5) from a thread in the given

handlerExecutorpool. - Complete the connection request callback with the parsed token.

(Notice the marvellous.substring(34)stripping the response header(s))

The code of getConnection is unchanged.

Streaming

Implementers interested in streaming the content to their callers can simply take a RequestHandler themselves. This is

what GatewayService#downloadThingy does.

void downloadThingy(RequestHandler handler, ExecutorService handlerExecutor) {

① asyncNonBlockingRequest(boundedServiceExecutor,

"http://localhost:7000",

/*headers*/ String.format(HEADERS_TEMPLATE, "GET", "download", "application/octet-stream", String.valueOf(0)),

new RequestHandler() {

@Override

public void received(byte[] data) {

if (handler != null)

if (handlerExecutor!=null) {

② handlerExecutor.submit(() -> handler.received(data));

} else {

handler.received(data);

}

}

@Override

public void completed() {

if (handler != null)

if (handlerExecutor!=null) {

③ handlerExecutor.submit(handler::completed);

} else {

handler.completed();

}

}

/* isCancelled and failed methods are trivial */

});

}

- Execute the HTTP request from a thread in the

boundedServiceExecutorpool. - Simply forward the data to the connection request callback.

- Complete the connection request callback when finished.

The code of getThingy handling the streaming of data is a tiny bit more complex because of the change from

CompletionHandler to RequestHandler and the handling of byte arrays, but not worthy of being included here.

We’re done with implementation changes.

Profiling

We’ve seen in the last entry that an asynchronous thread-blocking API doesn’t perform any better

than a synchronous thread-blocking one. Its latency is actually worse due to blocked threads.

Let’s compare with an asynchronous, non-thread-blocking API.

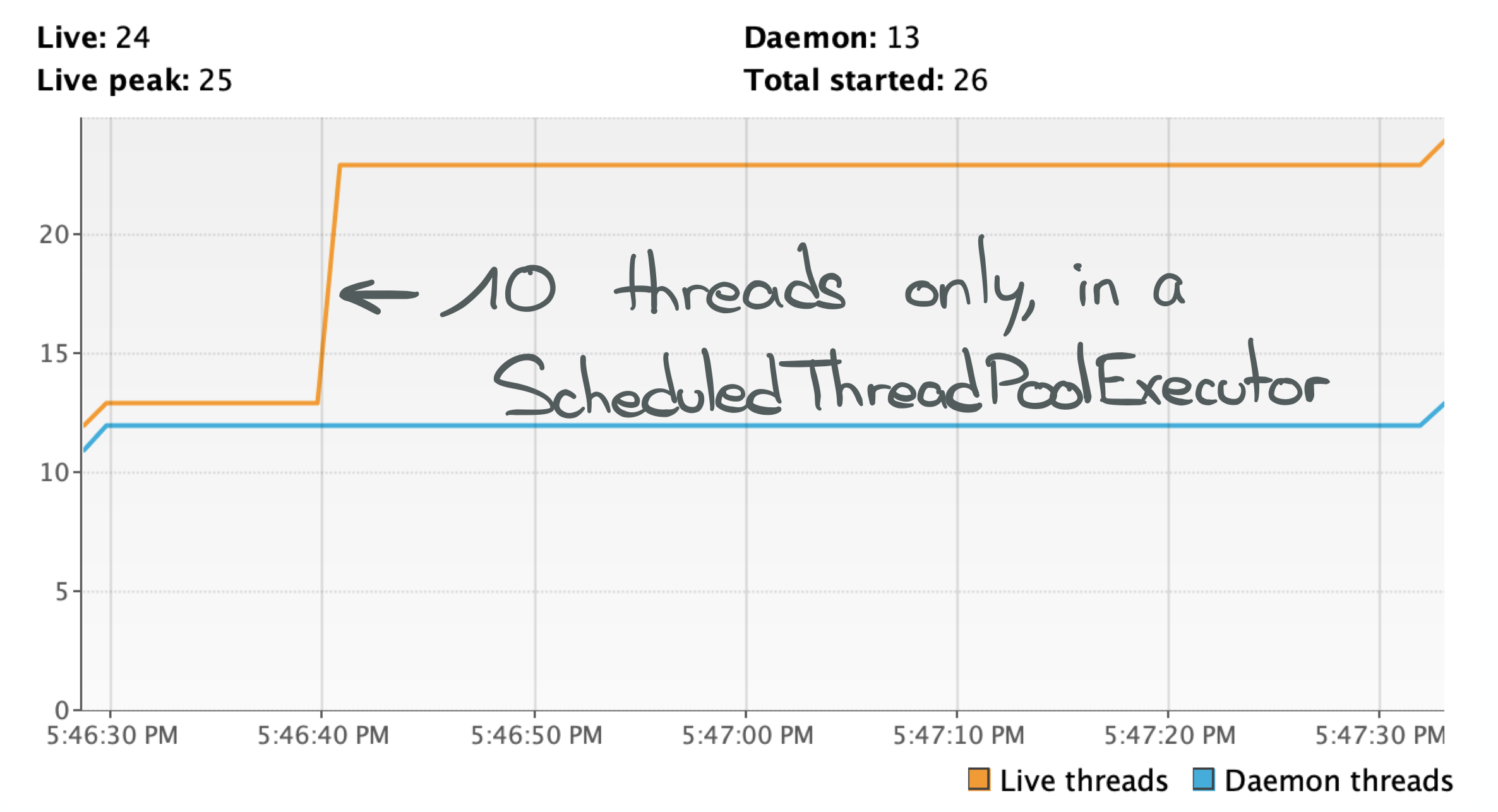

I’ve reduced the number of ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor from the last implementation from 3 to 1. The whole

simulation lasted less than a minute, like the first implementation.

This time only 10 threads were used.

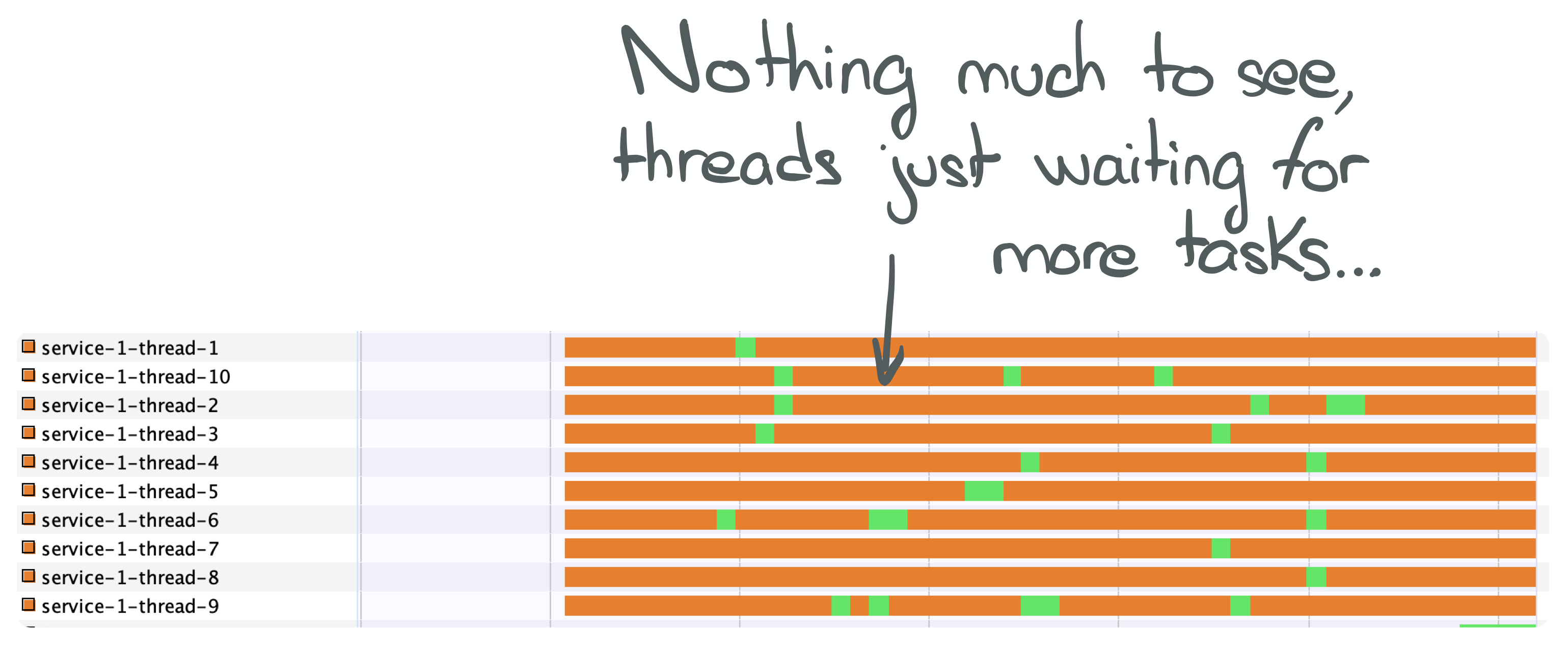

VisualVM confirms that the 10 threads were more than enough to handle such a small load. Indeed, the 10 threads of

this pool spend most of their time parked… We do see short bursts of execution to handle events (i.e.

asynchronous calls). But the tasks queue is drained quickly and the executor then parks the starved threads.

In fact, a single thread (e.g. Executors#newSingleThreadExecutor) could handle much more than those 200 connections.

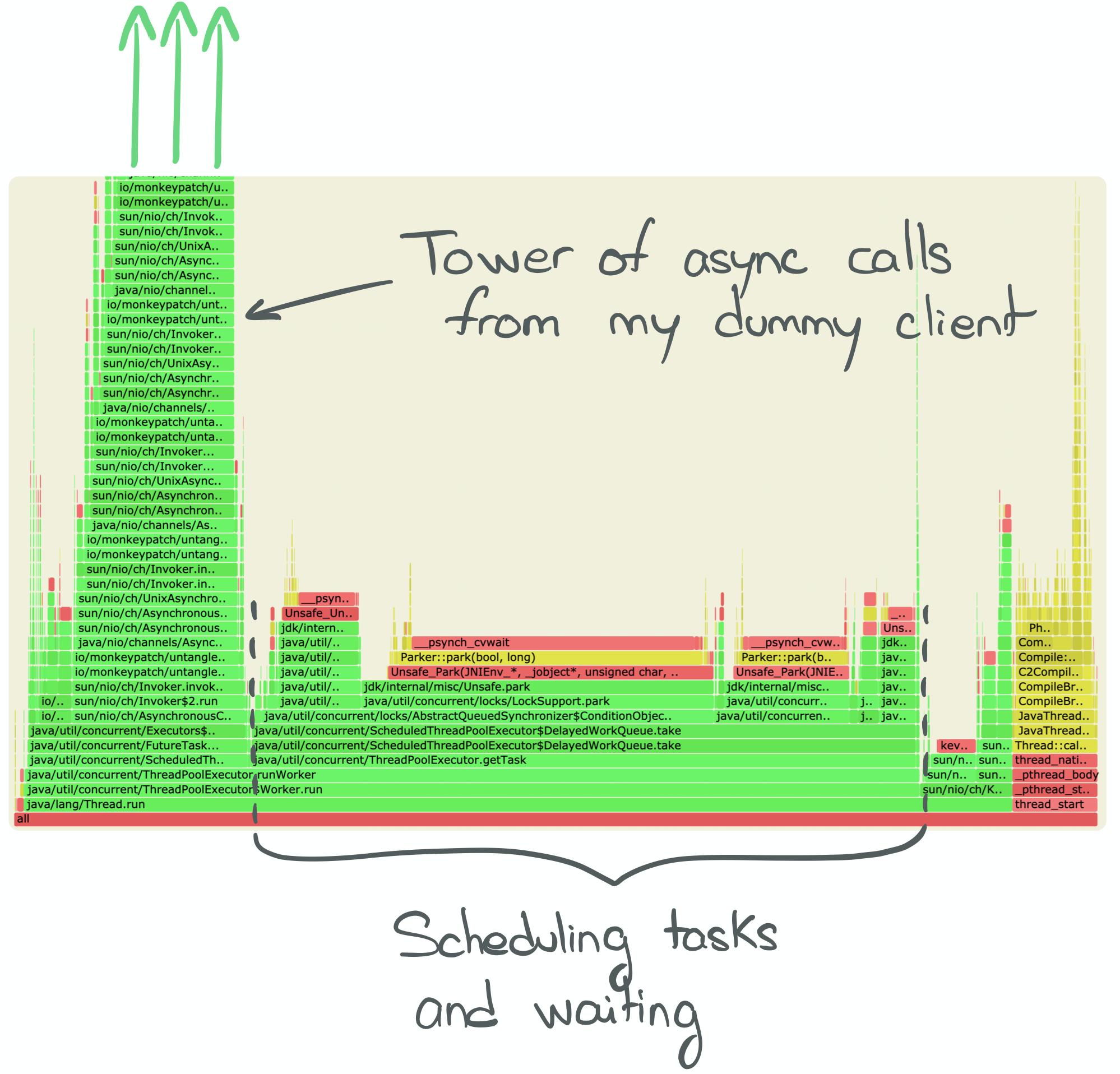

The statement above is supported by the following flame graph:

Scheduling tasks and awaiting to unpark threads dominates the execution time of this simulation. Which means our threads are underutilized.

Notice the giant tower of calls on the left? As said above, my implementation has a major drawback due to its recursive nature. The stack overflow is near…

It would have been wiser not to call the read/write methods of the channel recursively and instead submit them to the executor!

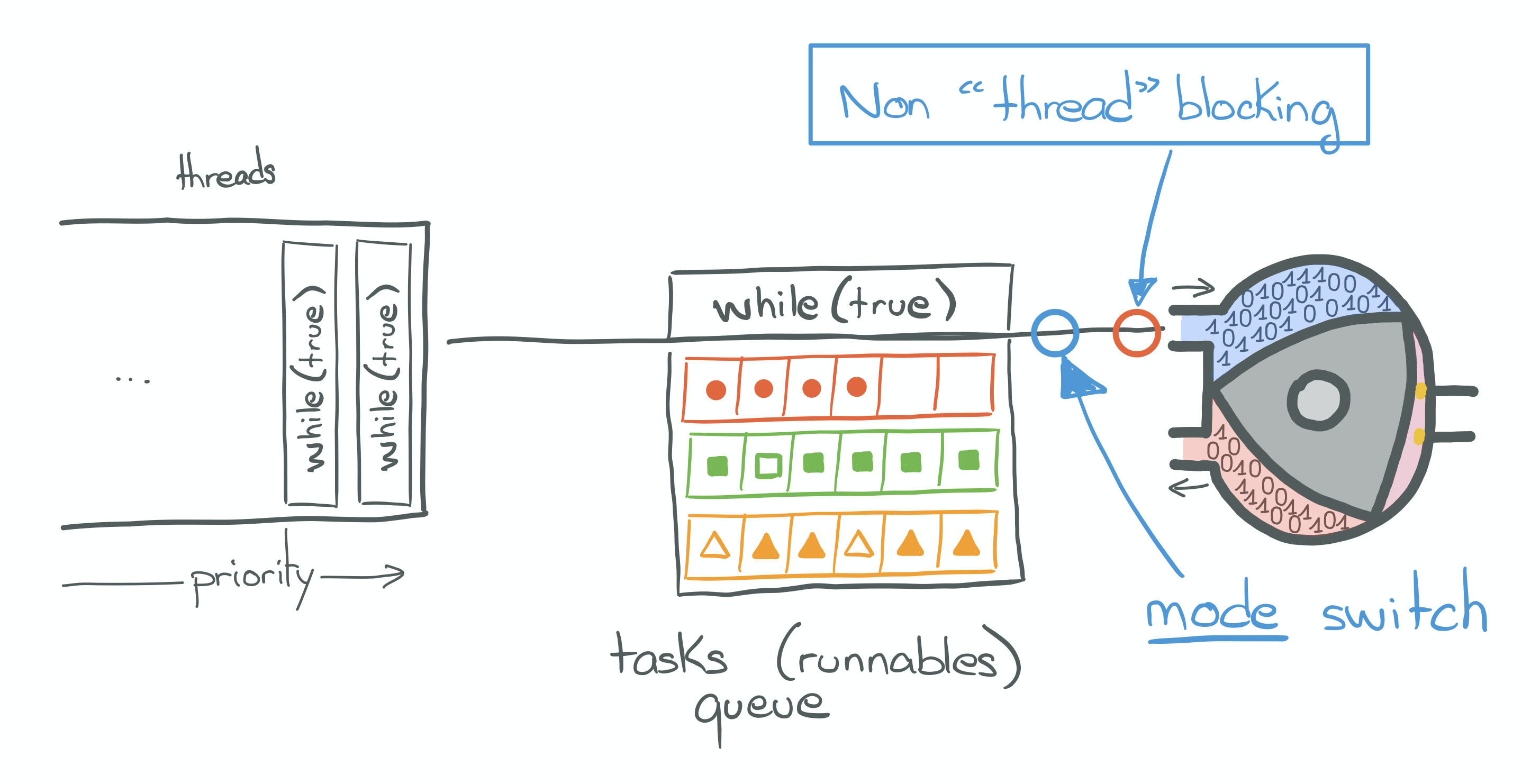

The value added of NIO is to provide context-switch free syscalls, eventually allowing to handle multiple channels

on a single thread. Those syscalls only require mode-switches.

Mode switches

When making blocking syscalls, the program running in userspace requests privileges in order to access the resources

it needs (see also: “Protection ring").

And because it is a blocking call, the state of execution of the thread has to be saved. Both operations are

atomically identified as a context-switch.

Truly non-thread-blocking asynchronous API allow efficient utilization of the physical resources by allowing a

program running in userspace to only request privileges. Contrary to blocking calls, the thread does not have to be

suspended: only the part relative to privilege request of a context switch is needed.

This operation is known as a mode switch.

Going further

As mentioned before, the implementation I have just shown is far from perfect and actually quite dumb: Not only is it not stack-safe, it is also inefficient.

Look how asyncNonBlockingRequest repetitively calls read, and write, even thought the number of bytes available to

be read or written may be zero. The threads are not blocked by each call for sure, but this implementation also

wastes a lot of CPU cycles issuing calls onto channel/file descriptors that may have nothing to offer.

Fortunately, the java.nio package provides a way to monitor file descriptors in order to ask or get notified when an

operation can be done, such as connecting, accepting connections, reading or writing.

More specifically, I could have used a java.nio.channels.Selector. In fact I did, in another part of

this repository. But it’s not where I wanted my talks nor this series to go.

You may still be interested in reading more about this API and the syscalls it may be based on:

select,poll,epollor its FreeBSD (OS X) equivalent,kqueue.

You can find more about file descriptors in this article, and epoll in this article.

I only have a basic understanding of how the syscalls mentioned above work. But I’m happy with what I know for the moment and to leave this implementation where it’s at. Because: 1) It is complex and 2) I’m not going to implement a Web server any time soon. And chances are you aren’t either.

Instead, you are probably going to decide to use any of the various flavors of Web servers available in the Java ecosystem.

You may end up using Spring WebFlux, Undertow, Vert.x, ServiceTalk, Armeria or the likes…

What do all theses have in common? Netty!

Netty is a wonderful piece of software. It’s a highly efficient, performant and optimized networking library. In fact, it’s probably true that Netty powers most of the JVM-based Web services and microservices out there in the world.

Netty is also very much an asynchronous API. It’s based on en EventLoop pattern,

and has various flavors of “transport” mechanisms to open, close, accept, read from and write to sockets. To

be more specific, it supports NIO transport (based on what you’ve seen above, but better), native epoll on Linux

hosts and native kqueue on BSD hosts. And it may provide an io_uring transport one day.

My point in saying this is that, although Netty is a fantastic library, it being asynchronous leaves us with in the same sad state of having to split our logic into pieces into callbacks, and manage the graph and dependencies between concurrent tasks.

Conclusion

Non-kernel-thread-blocking I/O calls are possible under the current JDK API. However, one has to write

asynchronous handlers.

As outlined in this post, asynchronous code is complex, but is also very much fragile.

I, for one, would rather avoid asynchronous API if given the choice. Alternatively, I’d like to have it wrapped

in an API I can reason about and build on top of, without pulling my hair out.

Luckily, there’s an API Specification for that! And several libraries which implement it and

provide composable, functional, declarative and lazy API. That’s quite a mouthful.

In the next part, we’ll re-implement our use-case using one of these libraries.

This blog uses Hypothesis for public and private (group) comments.

You can annotate or highlight words or paragraphs directly by selecting the text!

If you want to leave a general comment or read what others have to say, please use the collapsible panel on the right of this page.