November 28, 2017 — 19 minutes read

clojure REPL kotlin

Die Hard with a Vengeance — Water puzzle scene

This post is the first or a series where I explore Clojure features and start a discussion with my colleague Igor about Clojure and Kotlin.

This summer, Igor offered to make a live Kotlin demo of a nice problem he’s been working on that can serve as a fine exercise to discover and experiment a programming language: the Water pouring puzzle.

In this article I talk about the programming style I’ve used to find my solution: a data oriented, bottom-up approach, at the REPL.

Igor’s guideline offers a good starting point

on how OO and/or static typing (including myself when I switch to Java for

instance) would solve this problem: model the world.

Notice how, by following this recipe, you don’t get to handle or transform

any data until point 15 of about 30.

Although I understand how this is more usual, familiar and maybe the most straightforward way to do things for a majority of developers, to me this is a major drawback. It means that half of the time you are spending laying out things, hoping the Lego blocks will fall into place, thinking about types and safety when all you should be thinking about should be (IMO) how do I solve this particular problem.

After a few years of REPL driven development I know that I have a good tool to functionally, expressively and incrementally solve a problem.

This post is basically a transcript of my thought process as I was writing

a solver to the Water pouring puzzle at the REPL.

It was interesting to take the time to reflect and watch myself work as

I was proceeding, it took more time but it was definitely an interesting

experiment.

I setup the boilerplate first. (leiningen, dependencies, etc) and a namespace to work in:

At the REPL, the fundamental principle is: exploratory programming.

I don’t know how to find the solution to this problem (yet!),

all I have at this point is a namespace.

I must begin somewhere, so let’s start with some data: a glass has a total

capacity and a current state (0 by default), I need a collection of those.

I start at the REPL by declaring inital-state:

Then final-state to illustrate the target:

Pretty easy: each glass is a map and I put two of those in a vector.

Just thinking about the amount of code I would have to write in Java or Kotlin

just to get a short sample of data like this gives me goosebumps.

Kotlin might,

at some point,

have collection literals similar to those, or not.

There seems to be a debate inside the community whether this is a desired

feature or not, despite the clear winner of the community survey.

Communicating intent is an important part of a language and Kotlin’s debate

around collection literals seems to fall in the category of convenient syntax

vs intent. Why?

Because Kotlin’s designers have made the choice to support both mutable and

immutable collections as first class citizens. So how do you define what {}

is or [] is? Is it mutable or immutable?

The debate also seem to include considerations such as ordered/unordered and the

choice of syntax between lists and sets. Good luck figuring that out.

Clojure is based on first-class persistent data-structures so mutation is not and option, and its collection literals are easily identified:

()for lists (PersistentList)[]for vectors (PersistentVector){}for a maps (PersistentHashMap)#{}for sets (PersistentHashSet)

Want ordered/unordered variants? array-maps? queues? Sure, just use the

appropriate constructor, the collections you will use the most are available

as literals and it’s a burden not put on you, the developer.

View it as “only convenient” if you want to ditch the argument and discussion

altogether, but with mutation out of the way a whole class of problems are gone

once again, and the benefit of being able to just copy and paste

around printed representations of data-structures (in REPL or in logs) and

use them verbatim as code is priceless.

Alright, so the actions allowed to be performed on a glass are either to pour some quantity out of it, or to fill it with some quantity.

So I implement a pour function first:

This is a multi-arity function:

- The first implementation takes a glass as its only parameter and returns a new1 empty glass of the same capacity.

- The second implementation takes a glass as its first parameter and a quantity as its second parameter and returns a new glass poured out of the given quantity or poured out empty if it contains less than the given quantity.

- In the second arity, I destructure the first parameter (the glass) which

is a map, in order to get its

currentkey only, as I don’t care about itscapacity. associs (for short) a standard library function that returns a new map containing the newkey/valuemapping.

Don’t worry about the prefix notation, it’s not difficult, it’s just different, you’re not familiar with it, and you’ll get used to it.

Test pour:

- Pouring out empty a glass of capacity

5returns an empty glass of capacity5. - Pouring out

2from a glass of capacity8containing4returns a glass of capacity8containing2. - And pouring out

5from a glass of capacity8containing4just returns and empty glass, not-1.

Ignore the last nil in the results, it’s just the live code evaluation

plugin that prints it out as the result of the last println call.

Go ahead and play with it a little, even change the implementation above

if you will.

Now the fill function:

This is also a multi-arity function:

- The first implementation fills a glass up to its maximum capacity.

- The second implementation fills a glass up to its maximum capacity given a quantity to fill it with.

- Both return a new glass of course (not a copy!!!), we’re in immutable land here.

Test fill:

- Filling an empty glass returns a glass full.

- Filling

1into a glass of capacity8that already contains4returns a glass of capacity8containing5. - And filling

2into a glass of capacity8that already contains7returns a glass of capacity8that is full, not9.

Let’s take a break here.

One of the major benefits of a good REPL (and Clojure’s REPL is a good one), is the ability to explore: write one function at a time, execute it right away with a small amount of data, creating a really short feedback loop in order to explore multiple solutions.

In this blog post I use Klipse in order to present my iterative

process and let you play with the code.

This is nice for you to get a feel and try different inputs to my functions,

or write different implementations if you want to.

A good REPL is superior to TDD because it lets you write (or better: keep) tests that matter, get the result out of a function call and use it again as data that can populate your real tests.

But if you’ve tried other REPLs (ruby, python, node, etc.), you may be thinking that a REPL is not practical, because it forces you to copy/paste code all the time, go back and forth in you REPL’s history in order to retrieve past results and implementations just to change a few characters.

And this is where tooling is important.

Lots of Clojure developers use emacs (or cursive, an Intellij plugin) and

benefit from its integration with the REPL.

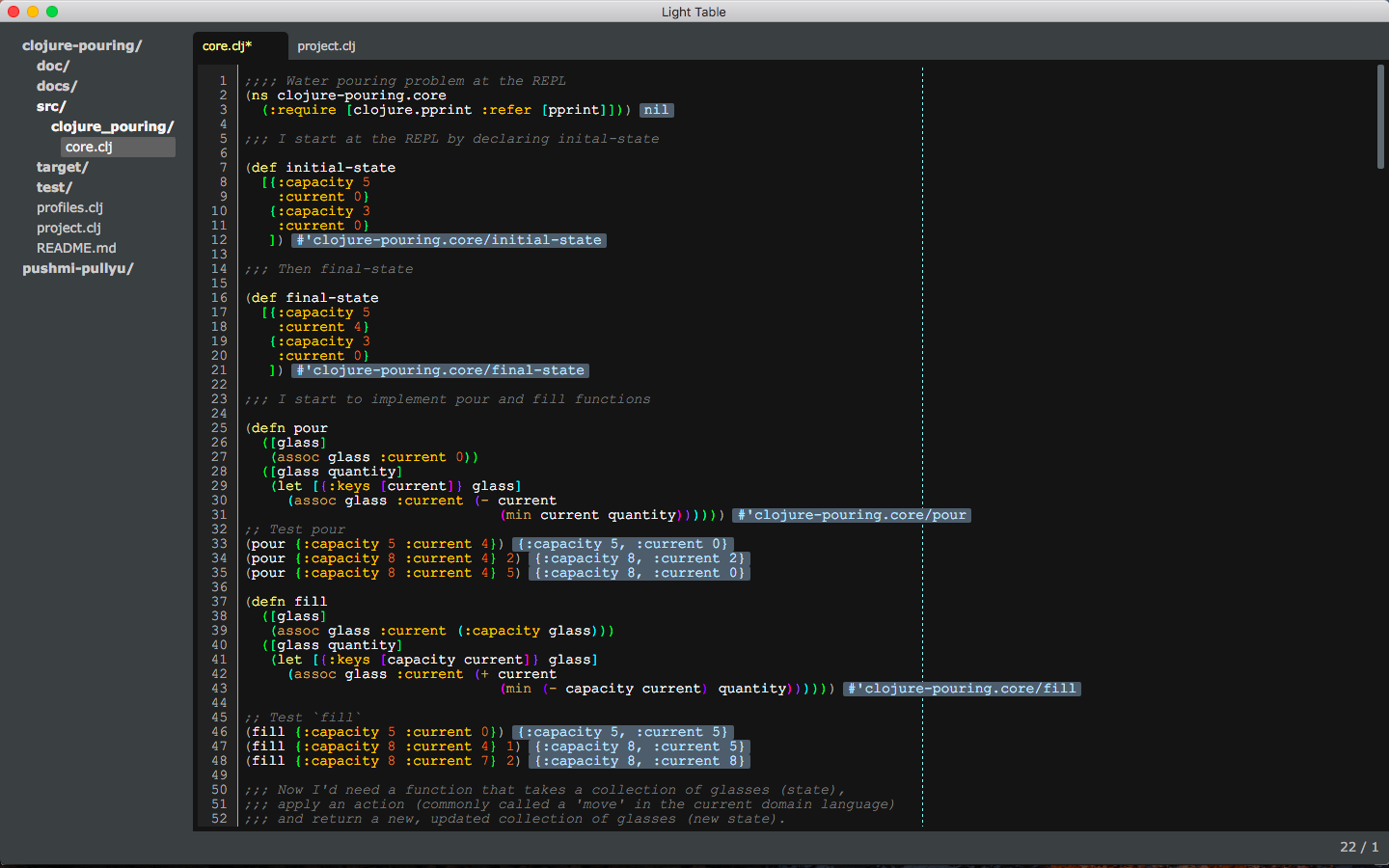

I, personnally, have been enjoying Light Table since 2013, and

this is a screenshot of my laptop while I’m working at the REPL:

Do you see the “blue” data? This is the result of evaluating a Clojure

expression in the editor itself.

This alone has made it difficult for me to switch to another editor ever since.

At the REPL, I type in data, I pass it to functions and I get the

result (which I use later as new input/expected output for other tests)

in front of my eyes.

I define new functions and make extensive use of “variable shadowing” to

modify the implementation of existing functions.

No classes, no types, no FactoryFactoryAbstractDelegateProxyPattern:

just data and functions…

I can hear you, static typing addict: BUT IT IS NOT SAFE!

Yes, I know, I just don’t care at this point! I told you, I’m exploring.

I want to go fast, iterate quickly, not model the whole universe and bang my

head against the type checker.

I can just rely on my tests for now and use simple assertions or specifications later (or now, but right now I’m not, obviously) to refine.

I’ve never had a shortest feedback loop in any other language I’ve used, this is pure gold.

Let’s continue our problem solving.

I have a pouring and a filling function.

Now I’d need a function that takes a collection of glasses (state),

apply an action (commonly called a ‘move’ in the current domain language)

and return a new, updated collection of glasses (new state).

What characterizes a move? It’s either an empty, pour or fill action

associated with glass indices:

- empty

fromthe nth glass - fill

tothe nth glass - pour

fromthe mth glasstothe nth glass

Expressivity matters, so maybe a move would be best represented by a map.

A map with a type that characterizes the move (empty, fill, pour) and

subjects that indicate the source / target / both of the move (from, to):

I’m beginning to think that a bit of Ad-hoc polymorphism would be great in order to dispatch on the type of move: let’s use multimethods.

The defmulti macro defines a new multimethod with the associated

dispatch function.

Which means that the ->move function will take two parameters, and the

dispatch function will choose the appropriate implementation.

In this case I dispatch based on the value associated to the :type key in the

move parameter.

A :empty move will dispatch to the ->move :empty multimethod.

A :fill move will dispatch to the ->move :fill multimethod.

A :pour move will dispatch to the ->move :pour multimethod.

update-in is a standard library

function that takes a data structure as a first parameter and “updates”

(immutable, remember?) the value nested at the path given by the second

parameter by applying to it the function supplied as the third parameter…

Don’t pretend you didn’t understand, just reread carefully.

Let’s take our ->move :empty multimethod as an example.

Since our move is an :empty, we destructure this parameter to get the

value at the :from key: the index of the glass in state that we want to

empty.

Once the glass has been fetched, update-in will evaluate the pour function

with the glass as its sole parameter.

Since I’ve implemented the 1-arity of the pour function so that it just

returns a new empty glass of same capacity, this result will replace

the glass in the state.

Let’s test ->move to “manually” go from initial-state to final-state:

It works!

I must now implement a function that, when given a collection of glasses, returns a collection of possible moves that can be applied to this state in order to produce a meaningful new collection of glasses.

Meaningful as in:

- not emptying an empty glass,

- not filling a glass that is full, and

- not pouring into ‘itself’, which gets us nowhere

I’m not going to explain everything, just look at the input and output in this

test of glasses->index:

The “indexing” works, now the function for listing moves:

Concatenate the list of moves able to empty the non-empty glasses, fill the non-full glasses and pour the non-empty glasses into the distinct non-full glasses.

Test available-moves:

I can get the list of moves that are practicable, now let’s explore the next glasses available from the current glasses.

Test explore:

Given a list of glasses (a state), returns the list of glasses I could get to (next states) by applying the moves that are available from my current state.

Given a node containing glasses and the sequence of moves leading to

them, return a list of successor nodes.

I evaluate the moves available from the current node’s glasses and for each one of them I return a new node consisting of the next state of glasses and the augmented list of move leading to it.

Test expand:

Nice, given glasses and the history of moves that led from an initial

state to these glasses, I can get the list of next states that are

possible, with their respective history of moves.

But at some point I might reach a state that I have already visited in the past… So it would be interesting to keep an index of the states that I have already visited in order to query it and avoid useless computation.

Let’s “backtract” the already visited nodes:

Test backtrack:

The first parameter of backtrack is a set, so contains? is O(1), not

O(n).

I’m almost there, right?

But I must stop searching at some point, so let’s identify a solution among

a set of candidates:

some is a standard library

function that returns the first logical true value of the predicate function

result.

My predicate function returns the list of moves leading to the current node

when the glasses of the node match the target glasses state, so if the

successors collection contains the solution, the list of moves to get

there is returned.

Test has-solution?:

And now the final part: I must compose the functions I have written so far in order to implement a solver.

This is bottom-up. I know I have all the parts of my solver in place and I have tested most of them along the way.

Let’s loop over glasses nodes, keeping track of the already visited ones, searching for a solution leading to the target state:

Test solver:

Test it again with a (seemingly) more complicated use case:

Functionally I could stop here because the problem is solved. But there are

some points that bother me, some vars names that don’t reflect what

piece of information they carry or some functions that could be broken into

smaller ones.

Let’s refactor a little:

Refactor ->move to better reflect domain:

Refactor expand by extracting the node builder:

Refactor solver by decomposing functions:

Let’s create a make-glass utility function:

Test make-glass:

Now a initialize function to create a vector of glasses from capacities or

capacities + quantities:

Test initialize:

Let’s extract the part of the solver that find the successors of a collection

of nodes into find-successors:

Test find-successors:

Let’s extract the part of the solver that filters out the successors that have

already been visited into filter-successors:

Test filter-successors:

We’re almost done. Let’s create a function to only keep a distinct set of

successors from a collection of candidates with get-unique-glasses.

Test distinct-glasses:

And now we can rewrite solver with these new pieces.

Test solver:

Implement -main:

It’s been a pretty long article in the end. Together we’ve implemented a function to solve the water pouring problem for an arbitrary list of glasses of some quantity in Clojure.

You can find the file I’ve used to write this exploratory work here, and the final version of the solver without all the evaluations here.

The thing that is the most interesting to me here is not the number of lines,

the safety or the provability of correctness.

What I want to stress out is the development at the REPL.

You can see in the repository that I didn’t even bother to write tests, because

I don’t plan to share this work, publish it or maintain it. Nonetheless it has

been tested.

I has been tested all the way from the beginning, at each function definition,

with data. You see, I didn’t need to use TDD, and I didn’t have to write some

temporary main function to pass inputs to the command line, and I didn’t need

to wait until I’ve assembled all the code together to try it fingers crossed.

Through the use of immutability, pure functions and first-class data literals

I feel like I can achieve more and iterate more quickly than with any other

language I’ve used.

I also argue that the Lisp syntax, although different, is an asset, because

there’s no cognitive load associated with it: no magical keywords, no mix of

parents, braces or brackets for structure: just lists as functions and data.

Footnote:

1: This it is not exactly a new glass as in ‘a copy’ but a new pointer to a persistent data structure, a concept also know as structural sharing (go back)

This blog uses Hypothesis for public and private (group) comments.

You can annotate or highlight words or paragraphs directly by selecting the text!

If you want to leave a general comment or read what others have to say, please use the collapsible panel on the right of this page.